library(tidyverse)

library(tidyfinance)

library(scales)Working with Stock Returns

You are reading Tidy Finance with R. You can find the equivalent chapter for the sibling Tidy Finance with Python here.

The main aim of this chapter is to familiarize yourself with the tidyverse for working with stock market data. We focus on downloading and visualizing stock data from data provider Yahoo Finance.

At the start of each session, we load the required R packages. Throughout the entire book, we always use the tidyverse (Wickham et al. 2019) package. In this chapter, we also load the tidyfinance package to download stock price data. This package provides a convenient wrapper for various quantitative functions compatible with the tidyverse and our book. Finally, the package scales (Wickham and Seidel 2022) provides nice formatting for axis labels in visualizations.

You typically have to install a package once before you can load it into your active R session. In case you have not done this yet, call, for instance, install.packages("tidyfinance").

Downloading Data

We first download daily prices for one stock symbol, e.g., the Apple stock (AAPL), directly from the data provider Yahoo Finance. To download the data, you can use the function download_data. In case this is the first time you use the package tidyfinance, you may be asked once to install some additional packages in the process of downloading the data. If you do not know how to use it, make sure you read the help file by calling ?download_data. We especially recommend taking a look at the examples section of the documentation.

In the following code, we request daily data from the beginning of 2000 to the end of the last year, which is a period of more than 20 years.

prices <- download_data(

type = "stock_prices",

symbols = "AAPL",

start_date = "2000-01-01",

end_date = "2024-12-31"

)

prices# A tibble: 6,288 × 8

symbol date volume open low high close adjusted_close

<chr> <date> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 AAPL 2000-01-03 535796800 0.936 0.908 1.00 0.999 0.842

2 AAPL 2000-01-04 512377600 0.967 0.903 0.988 0.915 0.771

3 AAPL 2000-01-05 778321600 0.926 0.920 0.987 0.929 0.782

4 AAPL 2000-01-06 767972800 0.948 0.848 0.955 0.848 0.715

5 AAPL 2000-01-07 460734400 0.862 0.853 0.902 0.888 0.749

# ℹ 6,283 more rows download_data(type = "stock_prices") downloads stock market data from Yahoo Finance. The function returns a data frame with eight self-explanatory columns: symbol, date, the daily volume (in the number of traded shares), the market prices at the open, high, low, close, and the adjusted price in USD. The adjusted prices are corrected for anything that might affect the stock price after the market closes, e.g., stock splits and dividends. These actions affect the quoted prices, but they have no direct impact on the investors who hold the stock. Therefore, we often rely on adjusted prices when it comes to analyzing the returns an investor would have earned by holding the stock continuously.

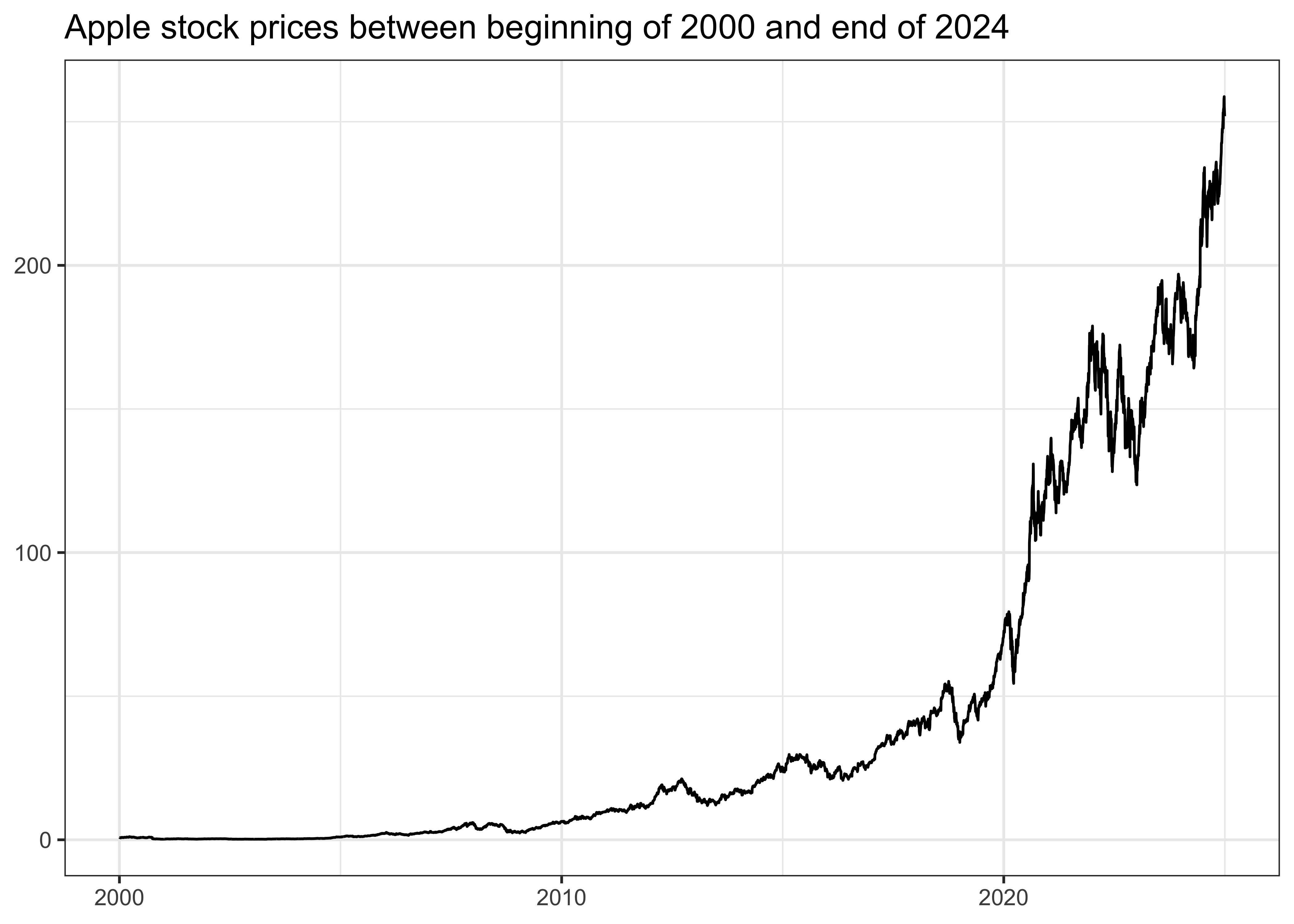

Next, we use the ggplot2 package (Wickham 2016) to visualize the time series of adjusted prices in Figure 1. This package takes care of visualization tasks based on the principles of the grammar of graphics (Wilkinson 2012).

Computing Returns

Instead of analyzing prices, we compute daily returns defined as \(r_t = p_t / p_{t-1} - 1\), where \(p_t\) is the adjusted price at the end of day \(t\). In that context, the function lag() is helpful by returning the previous value.

returns <- prices |>

arrange(date) |>

mutate(ret = adjusted_close / lag(adjusted_close) - 1) |>

select(symbol, date, ret)

returns# A tibble: 6,288 × 3

symbol date ret

<chr> <date> <dbl>

1 AAPL 2000-01-03 NA

2 AAPL 2000-01-04 -0.0843

3 AAPL 2000-01-05 0.0146

4 AAPL 2000-01-06 -0.0865

5 AAPL 2000-01-07 0.0474

# ℹ 6,283 more rowsThe resulting data frame has three columns, the last of which contains the daily returns (ret). Note that the first entry naturally contains a missing value (NA) because there is no previous price. Obviously, the use of lag() would be meaningless if the time series is not ordered by ascending dates. The command arrange() provides a convenient way to order observations in the correct way for our application. If you want to order observations by descending values, you could, for instance, use arrange(desc(ret)). Always check that your data has the desired structure before calling lag() or similar functions.

For the upcoming examples, we remove missing values as these would require separate treatment for many applications. For example, missing values can affect sums and averages by reducing the number of valid data points if not properly accounted for. In general, always ensure you understand why NA values occur and carefully examine if you can simply get rid of these observations.

returns <- returns |>

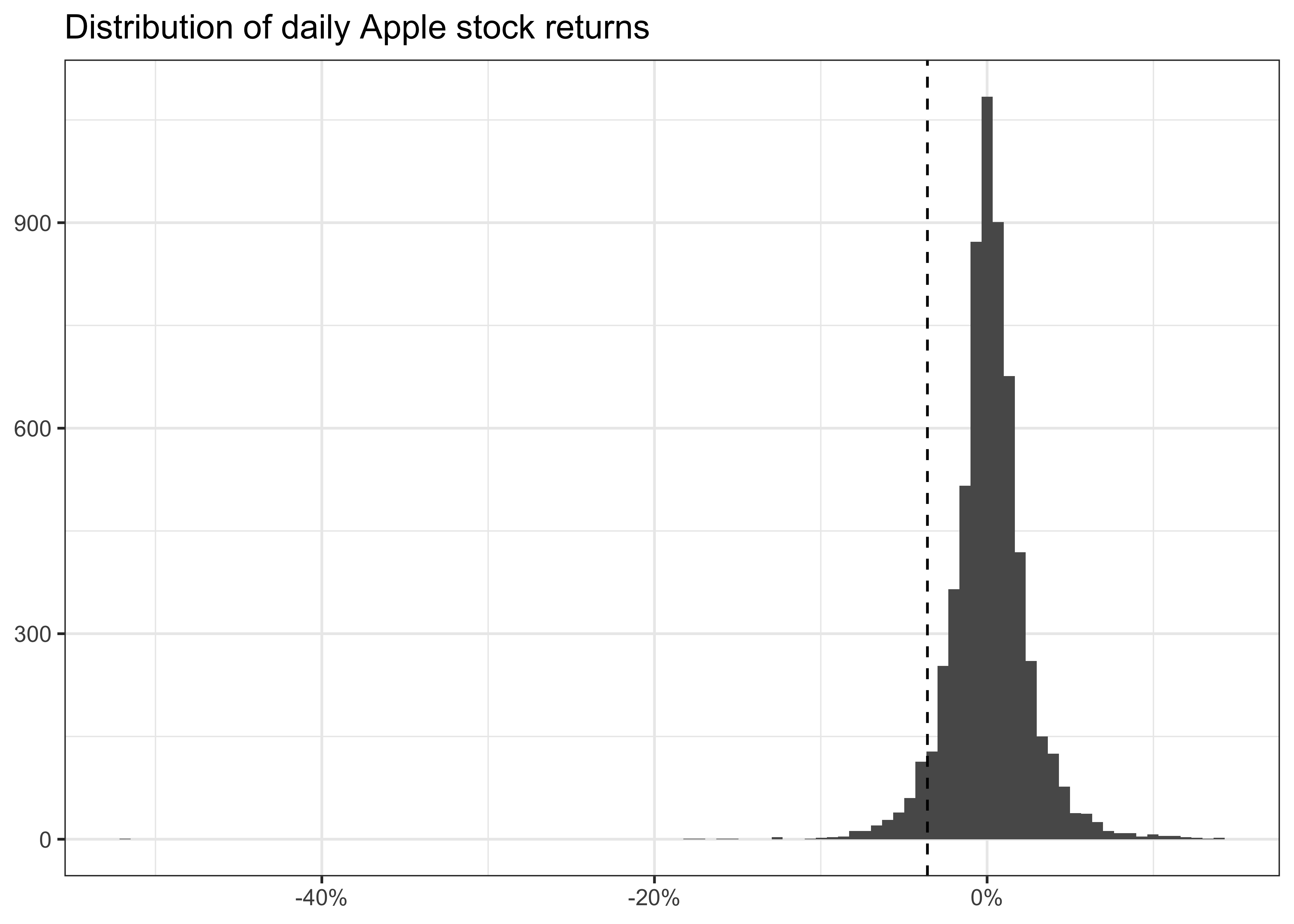

drop_na(ret)Next, we visualize the distribution of daily returns in a histogram in Figure 2. Additionally, we draw a dashed line that indicates the historical five percent quantile of the daily returns to the histogram, which is a crude proxy for the worst possible return of the stock with a probability of at most five percent. This quantile is closely connected to the (historical) value-at-risk, a risk measure commonly monitored by regulators. We refer to Tsay (2010) for a more thorough introduction to the stylized facts of financial returns.

quantile_05 <- quantile(returns$ret, probs = 0.05)

returns |>

ggplot(aes(x = ret)) +

geom_histogram(bins = 100) +

geom_vline(aes(xintercept = quantile_05),

linetype = "dashed"

) +

labs(

x = NULL,

y = NULL,

title = "Distribution of daily Apple stock returns"

) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = percent)Here, bins = 100 determines the number of bins used in the illustration and, hence, implicitly sets the width of the bins. Before proceeding, make sure you understand how to use the geom geom_vline() to add a dashed line that indicates the historical five percent quantile of the daily returns. Before proceeding with any data, a typical task is to compute and analyze the summary statistics for the main variables of interest.

returns |>

summarize(across(

ret,

list(

daily_mean = mean,

daily_sd = sd,

daily_min = min,

daily_max = max

)

))# A tibble: 1 × 4

ret_daily_mean ret_daily_sd ret_daily_min ret_daily_max

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 0.00122 0.0244 -0.519 0.139We see that the maximum daily return was 13.905 percent. Perhaps not surprisingly, the average daily return is close to but slightly above 0. In line with the illustration above, the large losses on the day with the minimum returns indicate a strong asymmetry in the distribution of returns.

You can also compute these summary statistics for each year individually by imposing group_by(year = year(date)), where the call year(date) returns the year. More specifically, the few lines of code below compute the summary statistics from above for individual groups of data defined by the values of the column year. The summary statistics, therefore, allow an eyeball analysis of the time-series dynamics of the daily return distribution.

returns |>

group_by(year = year(date)) |>

summarize(across(

ret,

list(

daily_mean = mean,

daily_sd = sd,

daily_min = min,

daily_max = max

),

.names = "{.fn}"

)) |>

print(n = Inf)# A tibble: 25 × 5

year daily_mean daily_sd daily_min daily_max

<dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 2000 -0.00346 0.0549 -0.519 0.137

2 2001 0.00233 0.0393 -0.172 0.129

3 2002 -0.00121 0.0305 -0.150 0.0846

4 2003 0.00186 0.0234 -0.0814 0.113

5 2004 0.00470 0.0255 -0.0558 0.132

6 2005 0.00349 0.0245 -0.0921 0.0912

7 2006 0.000949 0.0243 -0.0633 0.118

8 2007 0.00366 0.0238 -0.0702 0.105

9 2008 -0.00265 0.0367 -0.179 0.139

10 2009 0.00382 0.0214 -0.0502 0.0676

11 2010 0.00183 0.0169 -0.0496 0.0769

12 2011 0.00104 0.0165 -0.0559 0.0589

13 2012 0.00130 0.0186 -0.0644 0.0887

14 2013 0.000472 0.0180 -0.124 0.0514

15 2014 0.00145 0.0136 -0.0799 0.0820

16 2015 0.0000199 0.0168 -0.0612 0.0574

17 2016 0.000575 0.0147 -0.0657 0.0650

18 2017 0.00164 0.0111 -0.0388 0.0610

19 2018 -0.0000573 0.0181 -0.0663 0.0704

20 2019 0.00266 0.0165 -0.0996 0.0683

21 2020 0.00281 0.0294 -0.129 0.120

22 2021 0.00131 0.0158 -0.0417 0.0539

23 2022 -0.000970 0.0225 -0.0587 0.0890

24 2023 0.00168 0.0128 -0.0480 0.0469

25 2024 0.00120 0.0143 -0.0482 0.0726In case you wonder, the additional argument .names = "{.fn}" in across() determines how to name the output columns. It acts as a placeholder that gets replaced by the name of the function being applied (e.g., mean, sd, min, max) when creating new column names. The specification is rather flexible and allows almost arbitrary column names, which can be useful for reporting. The print() function controls the R console’s output options.

Scaling Up the Analysis

As a next step, we generalize the previous code so that all computations can handle an arbitrary number of symbols (e.g., all constituents of an index). Following tidy principles, it is quite easy to download the data, plot the price time series, and tabulate the summary statistics for an arbitrary number of assets.

This is where the tidyverse magic starts: Tidy data makes it extremely easy to generalize the computations from before to as many assets or groups as you like. The following code takes any number of symbols, e.g., symbol <- c("AAPL", "MMM", "BA"), and automates the download as well as the plot of the price time series. In the end, we create the table of summary statistics for all assets at once. For this example, we analyze data from all current constituents of the Dow Jones Industrial Average index.

symbols <- download_data(

type = "constituents",

index = "Dow Jones Industrial Average"

)

symbols# A tibble: 30 × 5

symbol name location exchange currency

<chr> <chr> <chr> <chr> <chr>

1 GS GOLDMAN SACHS GROUP INC Vereinigte Staaten New Yor… USD

2 UNH UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC Vereinigte Staaten New Yor… USD

3 MSFT MICROSOFT CORP Vereinigte Staaten NASDAQ USD

4 HD HOME DEPOT INC Vereinigte Staaten New Yor… USD

5 SHW SHERWIN WILLIAMS Vereinigte Staaten New Yor… USD

# ℹ 25 more rowsConveniently, tidyfinance provides the functionality to get all stock prices from an index for a specific point in time with a single call.

prices_daily <- download_data(

type = "stock_prices",

symbols = symbols$symbol,

start_date = "2000-01-01",

end_date = "2023-12-31"

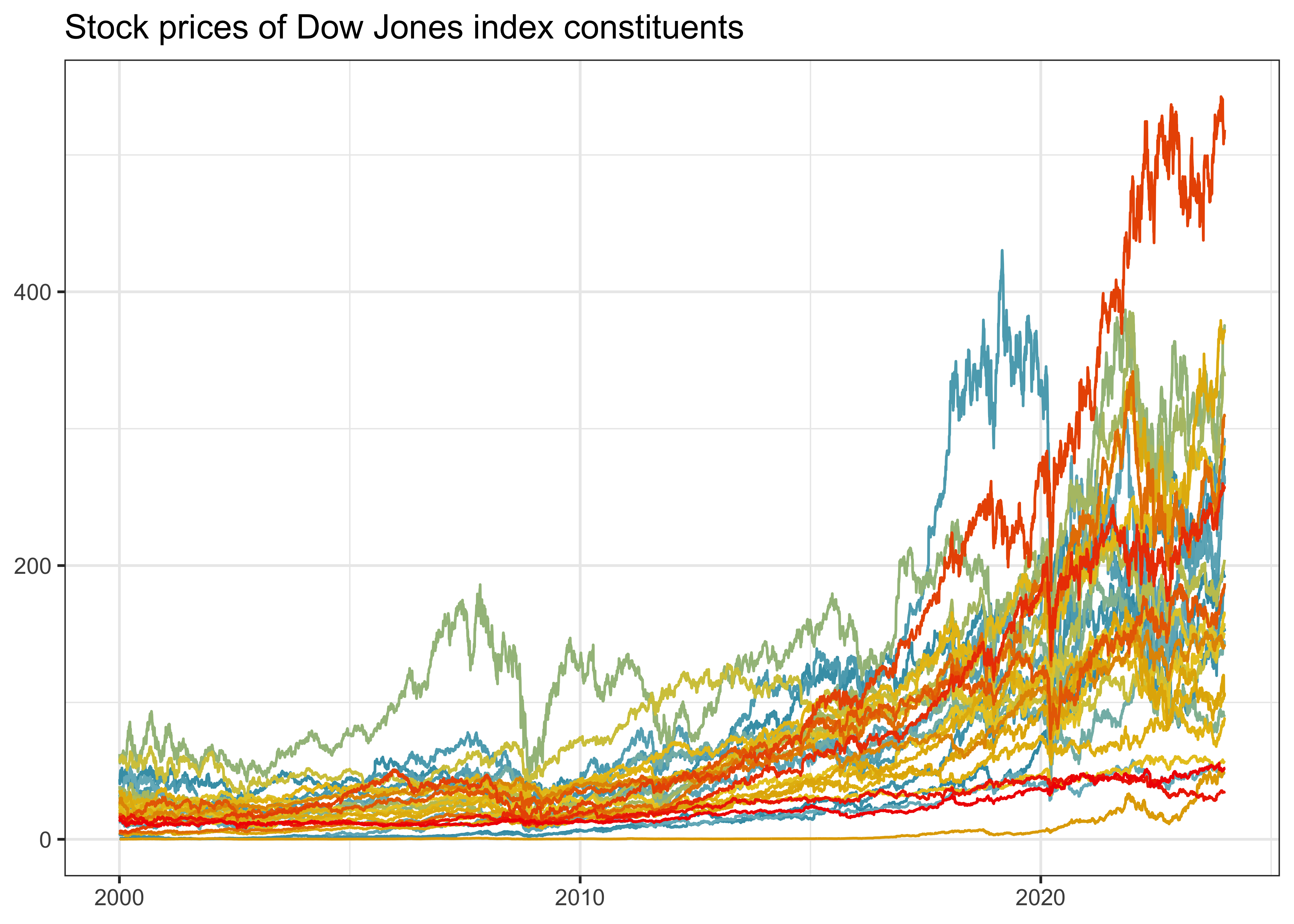

)The resulting data frame contains 177925 daily observations for GS, UNH, MSFT, HD, SHW, V, CAT, MCD, AMGN, AXP, CRM, TRV, IBM, JPM, AAPL, HON, AMZN, PG, CVX, BA, JNJ, MMM, NVDA, DIS, WMT, MRK, KO, NKE, CSCO, VZ different stocks. Figure 3 illustrates the time series of the downloaded adjusted prices for each of the constituents of the Dow index. Make sure you understand every single line of code! What are the arguments of aes()? Which alternative geoms could you use to visualize the time series? Hint: if you do not know the answers try to change the code to see what difference your intervention causes.

prices_daily |>

ggplot(aes(

x = date,

y = adjusted_close,

color = symbol

)) +

geom_line() +

labs(

x = NULL,

y = NULL,

color = NULL,

title = "Stock prices of Dow Jones index constituents"

) +

theme(legend.position = "none")Do you notice the small differences relative to the code we used before? All we needed to do to illustrate all stock symbols simultaneously is to include color = symbol in the ggplot aesthetics. In this way, we generate a separate line for each symbol. Of course, there are simply too many lines on this graph to identify the individual stocks properly, but it illustrates our point of how to generalize a specific analysis to an arbitrage number of subjects quite well.

The same holds for stock returns. Before computing the returns, we use group_by(symbol) such that the mutate() command is performed for each symbol individually. The same logic also applies to the computation of summary statistics: group_by(symbol) is the key to aggregating the time series into symbol-specific variables of interest.

returns_daily <- prices_daily |>

group_by(symbol) |>

mutate(ret = adjusted_close / lag(adjusted_close) - 1) |>

select(symbol, date, ret) |>

drop_na(ret)

returns_daily |>

group_by(symbol) |>

summarize(across(

ret,

list(

daily_mean = mean,

daily_sd = sd,

daily_min = min,

daily_max = max

),

.names = "{.fn}"

)) |>

print(n = Inf)# A tibble: 30 × 5

symbol daily_mean daily_sd daily_min daily_max

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 AAPL 0.00122 0.0247 -0.519 0.139

2 AMGN 0.000493 0.0194 -0.134 0.151

3 AMZN 0.00107 0.0315 -0.248 0.345

4 AXP 0.000544 0.0227 -0.176 0.219

5 BA 0.000628 0.0222 -0.238 0.243

6 CAT 0.000724 0.0203 -0.145 0.147

7 CRM 0.00119 0.0266 -0.271 0.260

8 CSCO 0.000322 0.0234 -0.162 0.244

9 CVX 0.000511 0.0175 -0.221 0.227

10 DIS 0.000414 0.0194 -0.184 0.160

11 GS 0.000557 0.0229 -0.190 0.265

12 HD 0.000544 0.0192 -0.287 0.141

13 HON 0.000497 0.0191 -0.174 0.282

14 IBM 0.000297 0.0163 -0.155 0.120

15 JNJ 0.000379 0.0121 -0.158 0.122

16 JPM 0.000606 0.0238 -0.207 0.251

17 KO 0.000318 0.0131 -0.101 0.139

18 MCD 0.000536 0.0145 -0.159 0.181

19 MMM 0.000363 0.0151 -0.129 0.126

20 MRK 0.000371 0.0166 -0.268 0.130

21 MSFT 0.000573 0.0193 -0.156 0.196

22 NKE 0.000708 0.0193 -0.198 0.155

23 NVDA 0.00175 0.0376 -0.352 0.424

24 PG 0.000362 0.0133 -0.302 0.120

25 SHW 0.000860 0.0180 -0.208 0.153

26 TRV 0.000555 0.0181 -0.208 0.256

27 UNH 0.000948 0.0196 -0.186 0.348

28 V 0.000933 0.0185 -0.136 0.150

29 VZ 0.000238 0.0151 -0.118 0.146

30 WMT 0.000323 0.0148 -0.114 0.117Note that you are now also equipped with all tools to download price data for each symbol listed in the S&P 500 index with the same number of lines of code. Just use symbol <- download_data(type = "constituents", index = "S&P 500"), which provides you with a data frame that contains each symbol that is (currently) part of the S&P 500. However, don’t try this if you are not prepared to wait for a couple of minutes because this is quite some data to download!

Different Frequencies

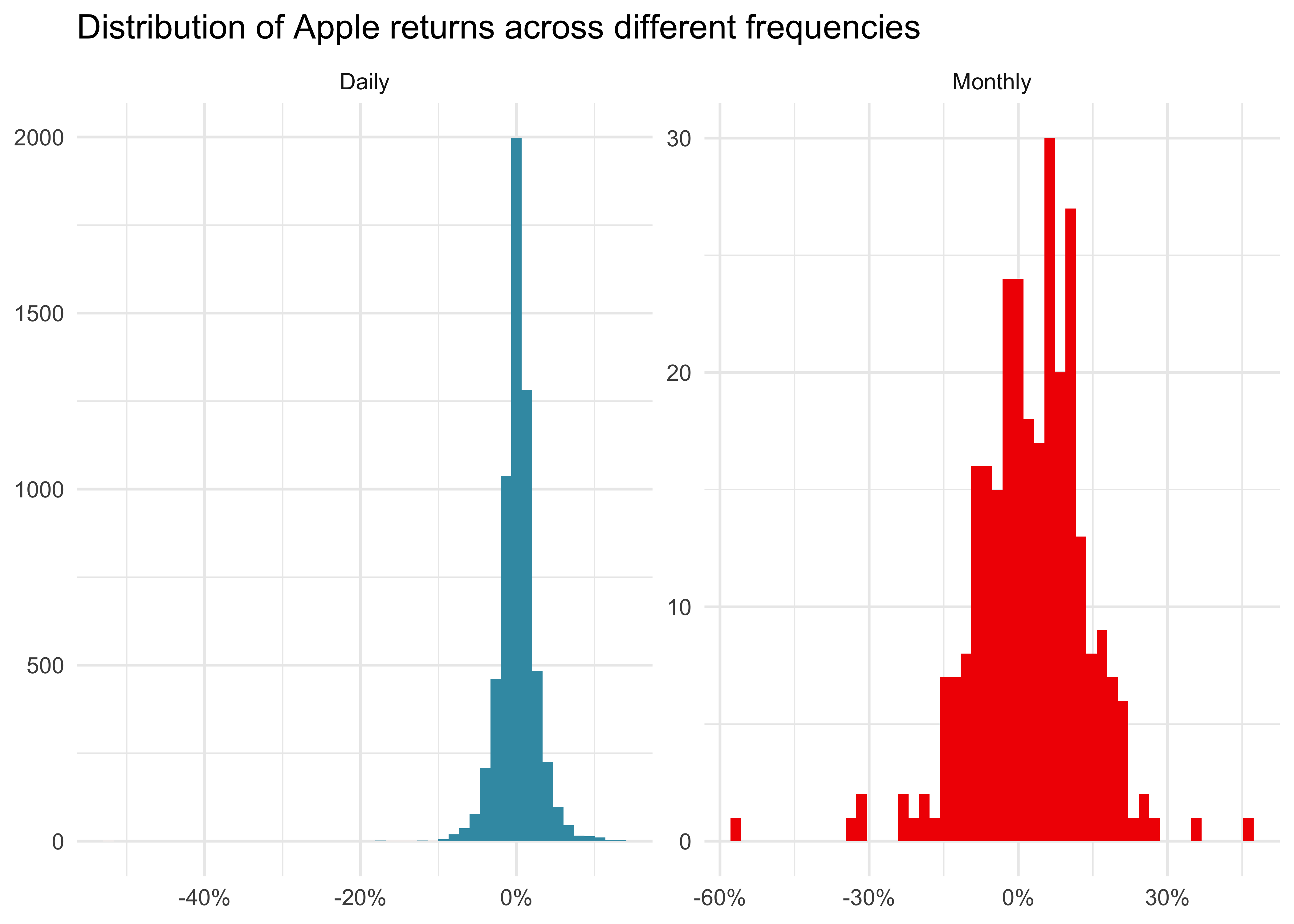

Financial data often exists at different frequencies due to varying reporting schedules, trading calendars, and economic data releases. For example, stock prices are typically recorded daily, while macroeconomic indicators such as GDP or inflation are reported monthly or quarterly. Additionally, some datasets are recorded only when transactions occur, resulting in irregular timestamps. To compare data meaningfully, we have to align different frequencies appropriately. For example, to compare returns across different frequencies, we use annualization techniques.

So far, we have worked with daily returns, but we can easily convert our data to other frequencies. Let’s create monthly returns from our daily data:

returns_monthly <- returns_daily |>

mutate(date = floor_date(date, "month")) |>

group_by(symbol, date) |>

summarize(

ret = prod(1 + ret) - 1,

.groups = "drop"

)In this code, we first group the data by symbol and month and then compute monthly returns by compounding the daily returns: \((1+r_1)(1+r_2)\ldots(1+r_n)-1\). To visualize how return characteristics change across different frequencies, we can compare histograms as in Figure 4:

apple_returns <- bind_rows(

returns_daily |>

filter(symbol == "AAPL") |>

mutate(frequency = "Daily"),

returns_monthly |>

filter(symbol == "AAPL") |>

mutate(frequency = "Monthly")

)

apple_returns |>

ggplot(aes(x = ret, fill = frequency)) +

geom_histogram(position = "identity", bins = 50) +

labs(

x = NULL,

y = NULL,

fill = "Frequency",

title = "Distribution of Apple returns across different frequencies"

) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = percent) +

theme_minimal() +

facet_wrap(~ frequency, scales = "free") +

theme(legend.position = "none")Other Forms of Data Aggregation

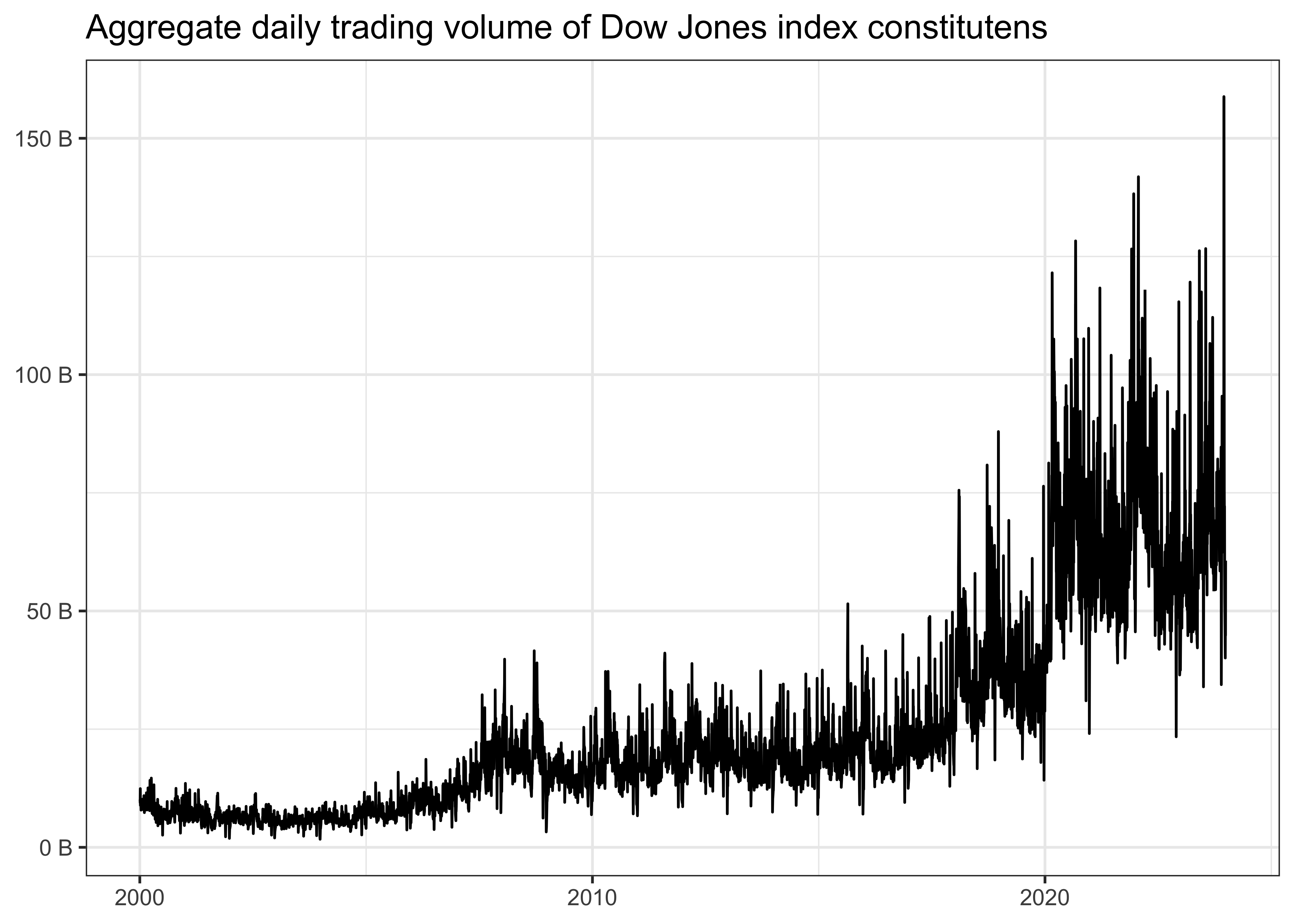

Of course, aggregation across variables other than symbol or date can also make sense. For instance, suppose you are interested in answering questions like: Are days with high aggregate trading volume likely followed by days with high aggregate trading volume? To provide some initial analysis on this question, we take the downloaded data and compute aggregate daily trading volume for all Dow index constituents in USD. Recall that the column volume is denoted in the number of traded shares. Thus, we multiply the trading volume with the daily adjusted closing price to get a proxy for the aggregate trading volume in USD. Scaling by 1e-9 (R can handle scientific notation) denotes daily trading volume in billion USD.

trading_volume <- prices_daily |>

group_by(date) |>

summarize(trading_volume = sum(volume * adjusted_close))

trading_volume |>

ggplot(aes(x = date, y = trading_volume)) +

geom_line() +

labs(

x = NULL, y = NULL,

title = "Aggregate daily trading volume of Dow Jones index constitutens"

) +

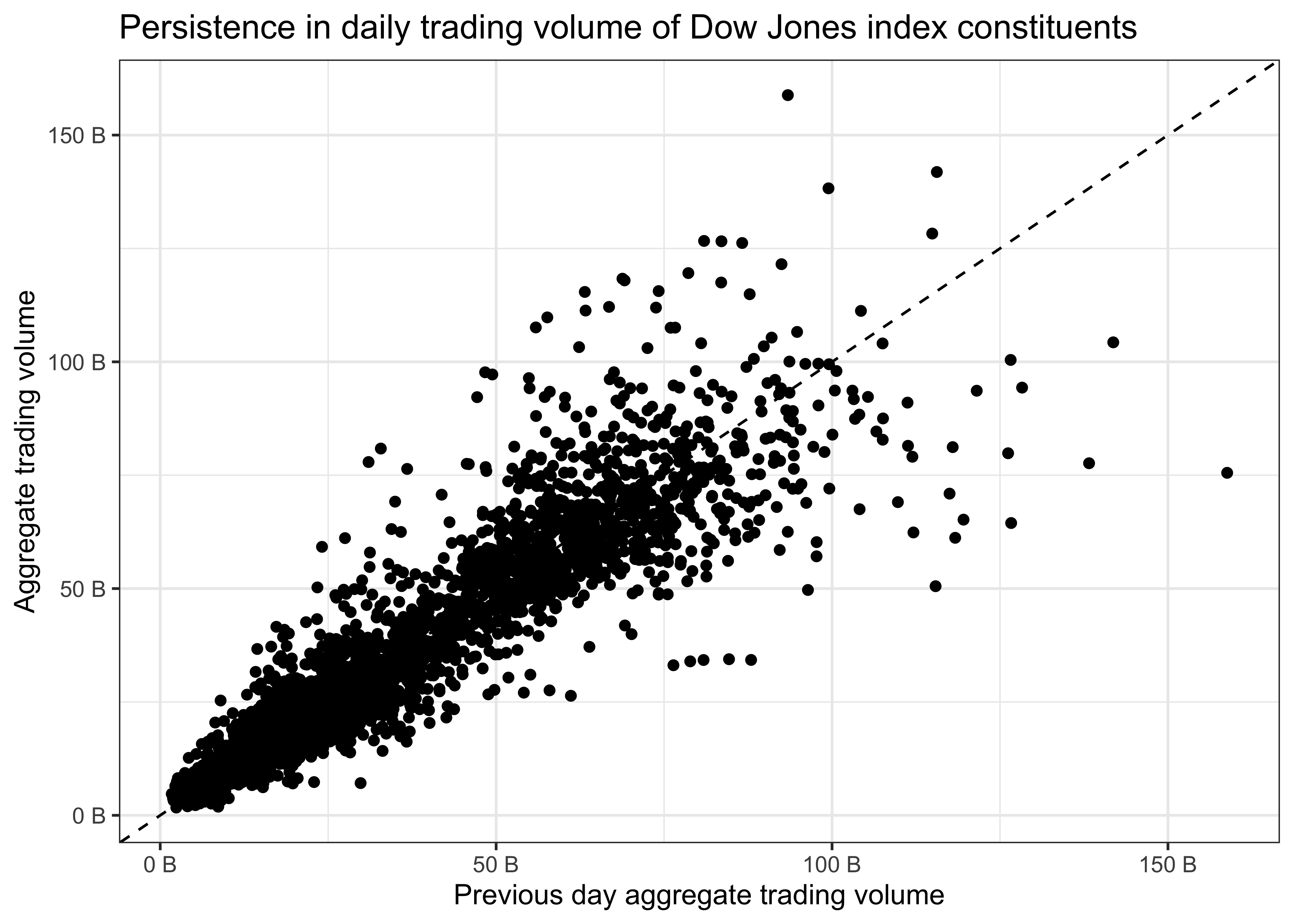

scale_y_continuous(labels = unit_format(unit = "B", scale = 1e-9))Figure 5 indicates a clear upward trend in aggregated daily trading volume. In particular, since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, markets have processed substantial trading volumes, as analyzed, for instance, by Goldstein, Koijen, and Mueller (2021). One way to illustrate the persistence of trading volume would be to plot volume on day \(t\) against volume on day \(t-1\) as in the example below. In Figure 6, we add a dotted 45°-line to indicate a hypothetical one-to-one relation by geom_abline(), addressing potential differences in the axes’ scales.

trading_volume |>

ggplot(aes(x = lag(trading_volume), y = trading_volume)) +

geom_point() +

geom_abline(aes(intercept = 0, slope = 1),

linetype = "dashed"

) +

labs(

x = "Previous day aggregate trading volume",

y = "Aggregate trading volume",

title = "Persistence in daily trading volume of Dow Jones index constituents"

) +

scale_x_continuous(labels = unit_format(unit = "B", scale = 1e-9)) +

scale_y_continuous(labels = unit_format(unit = "B", scale = 1e-9))Warning: Removed 1 rows containing missing values (`geom_point()`).Do you understand where the warning ## Warning: Removed 1 rows containing missing values (geom_point). comes from and what it means? Purely eye-balling reveals that days with high trading volume are often followed by similarly high trading volume days.

Key Takeaways

- You can use the

tidyversein R to efficiently analyze stock market data using consistent and scalable workflows. - The

tidyfinanceR package allows seamless downloading of historical stock prices and index data directly from Yahoo Finance. - Tidy data principles enable efficient analysis of financial data.

- Adjusted stock prices provide a more accurate reflection of investor returns by accounting for dividends and stock splits.

- Summary statistics such as mean, standard deviation, and quantiles offer insights into stock return behavior over time.

- Visualizations created with

ggplot2help identify trends, volatility, and return distributions in financial time series. - Tidy data principles make it easy to scale financial analyses from a single stock to entire indices like the Dow Jones or S&P 500.

- Consistent workflows form the foundation for advanced financial analysis.

Exercises

- Download daily prices for another stock market symbol of your choice from Yahoo Finance using

download_data()from thetidyfinancepackage. Plot two time series of the symbol’s un-adjusted and adjusted closing prices. Explain any visible differences. - Compute daily net returns for an asset of your choice and visualize the distribution of daily returns in a histogram using 100 bins. Also, use

geom_vline()to add a dashed red vertical line that indicates the 5 percent quantile of the daily returns. Compute summary statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum) for the daily returns. - Take your code from the previous exercises and generalize it such that you can perform all the computations for an arbitrary number of symbols (e.g.,

symbol <- c("AAPL", "MMM", "BA")). Automate the download, the plot of the price time series, and create a table of return summary statistics for this arbitrary number of assets. - To facilitate the computation of the annualization factor, write a function that takes a vector of return dates as input and determines the frequency before returning the appropriate annualization factor.

- Are days with high aggregate trading volume often also days with large absolute returns? Find an appropriate visualization to analyze the question using the symbol

AAPL.